I first learned of the Kuzma Stogi at the 1993 Winter CES in Las Vegas. In VPI's room at the Sahara, a portly, black tonearm was sitting proudly atop the new VPI TNT Series 3 turntable. Pointing straight at me from the center of its massive, exceptionally stout frame was a tapered armtube the diameter of a swollen thumb. The fact that this unknown (to me) tonearm was chosen to sit atop a turntable as respected as the TNT told me I was looking at a serious new product. VPI's Harry Weisfeld was standing nearby, beaming as usual, to answer the barrage of questions that sprang from my lips as I leaned over for a closer inspection. Who? What? Where? When? Why? How much?

As I tried to inconspicuously wipe the drool from my lower lip, a now smiling Harry told me that the tonearm I was ogling was the Stogi Reference, which is manufactured in the small Eastern European country of Slovenia by a company known as Kuzma Audio Komponente. That was the last I heard or saw of the Kuzma Stogi.

Until the 1994 WCES, when I strode into the Acoustic Sounds room to chat with Chad Kassem. It was there, in this vinyl-lover's Tiffany's, that I spotted the less-expensive Stogi mounted on a beautiful, solid-oak–plinthed Kuzma Stabi turntable. The combination was serving as the source for some of the most natural, compelling, and visceral sound I've ever heard from a pair of Sound-Lab electrostatic speakers. I stayed—to enjoy not only Chad's recent reissue of Lightnin' Hopkins' 1963 bare-to-the-bones blues on Goin' Away (Prestige Bluesville, now Analog Productions AAPB 014—just buy it!), but the striking naturalness of its presentation. That sound remained in my memory for months after the last audiophile-approved AC-power cord had been unplugged from a wall outlet in a small room somewhere in the Sahara Hotel's bi-level complex.

Not long after my return home from Las Vegas, I phoned Tom Norton in Santa Fe and Muse's Kevin Halverson to arrange the loan of a Stabi and Stogi for review.

Setup

Within a few months, a large carton arrived at my door in San Diego. As I eagerly but carefully unpacked the boxes and sorted and identified the parts, I recalled Muse's Kevin Halverson's assurance that setup of the Kuzma Stabi was a snap. It was. In fact, the most time-consuming aspect of the operation was the adding, drop by drop, of the viscous silicone oil to the four spring reservoirs (it took about half an hour). I used a toothpick as a depth gauge to ensure that the surface of the oil was the recommended distance (10–15mm) below the top edge of the reservoir.

I encountered no problems in this or subsequent stages of setup. The instructions were clear, and the many illustrations will guide even hamfisted audiophiles error-free through the process. The pre-drilled mounting board rendered installation of the Stogi tonearm similarly stress-free.

The 23¾" W by 15¾" D top shelf of a RoomTune ClampRack was just the right size for the Stabi centered on the top plate of a Bright Star Big Rock. With the Stabi so situated, it took only a few minutes to level it via its three pointed feet, route the tonearm cables, fine-tune the suspension, and adjust the tonearm and cartridge. I located the power supply, which controls the turntable and is connected to it via a long cable terminated in a five-pin DIN plug, on the lowest shelf of the ClampRack. This placement ensured that I'd get some exercise, since each time I wanted to change or flip records I had to bend down to turn the motor off, stand upright to make the change, and bend down again to turn the motor back on. During the course of my evaluation, I figure I went through this routine more than 4500 times. Funny thing, though—my waist size has remained the same.

With a record clamped in place, the platter's height should be adjusted to where it rotates between 1.5mm and 2.5mm above the plinth. I settled on 2mm (the thickness of seven Stereophile business cards), and made final adjustments by turning the motor on and twiddling with the four top-mounted spring assemblies until the bottom of the platter was just touching the top of the stack of business cards as I moved them around its circumference.

The Stabi's record clamp is one of the most effective I've used. A 1"-diameter, hard-plastic (Delrin?) washer with a convex top surface is placed over the threaded spindle and left there. When you go to play a record, you place it on the platter, where it teeter-totters over the washer until the 3¼"-diameter, saucer-shaped record clamp is screwed down, forcing the record down on the washer and flat against the composite material covering the surface of the platter. Different record thicknesses and severities of "dish" determine the degree of clamp tightening. Most of the records I played required from five to seven half-turns. With the exception of a hopelessly edge-warped Thelonious Monk LP, every record I played in this evaluation became a flat record.

The Stabi's motor has sufficient torque to keep the platter turning even during a heavy-handed cleaning of a record with a Discwasher preener. Changing speeds is as simple as turning the speed-control knob on the power supply from 33 to 45—neat and foolproof, since there are no drive belts to move about on a pulley, or any other such ministrations. Fine-speed adjustments are controlled by a DIP switch inside the power supply, accessible by removing the power supply's front right rubber foot. With a strobe disc on the platter, speed is adjusted, in small stages, according to the position of the switches.

Cartridge installation and alignment went without a hitch, due to the Stogi tonearm's straightforward design. I used a Dennesen Soundtractor protractor to set overhang on all the cartridges used in this review (footnote 1). This step was facilitated by the small etched circle in the top of the tonearm frame identifying the exact pivot point of the arm. Tracking force was easily set using the one-piece counterweight, secured by tightening one of the three small set screws. Checking settings against my Shure SFG-2 stylus-force gauge indicated that accuracy within a fraction of a gram can be obtained by following the guidelines set forth in the instruction manual.

I adjusted bias using a simple nylon thread and sliding counterweight arrangement. Kevin Halverson and the manufacturer recommend (and I concur) that bias be set with the stylus actually riding in the tracking bands of a test record instead of on the surface of the usual blank band. Adjust bias until you get equal mistracking from each channel on the heavily modulated bands, and you're set (footnote 2). Another adjustment and a tweak—both of which can be made to the tonearm without fuss—are, respectively, cueing height and removing the finger lift.

Arm height and/or VTA is adjusted by loosening a set screw in the tonearm base and physically raising or lowering the arm. Unfortunately, fine VTA adjustments made while a record is playing aren't possible with this arrangement. However, you can make repeatable VTA settings with little effort. Here's how I did it: After reading in the instruction manual that raising or lowering the tonearm pillar approximately 3mm (1/8") will change the angle between the record surface and stylus by 1°, I established a zero-point reference, with the bottom of the tonearm parallel with the surface of a "standard" record. Using a General No.300 stainless-steel machinist's rule, I measured (and made a note of) the distance from the surface of the armboard to the top of the armrest.

This was my zero-point reference, which I marked on the arm pillar with a red Sharpie Ultra Fine Point marker. I then added 1/8" to this initial reading, raised the tonearm the prescribed amount, and marked the pillar with a black Sharpie. By so doing, I had marked the pillar, indicating the height to which the tonearm should be raised to change the VTA by 1°. I continued to raise the tonearm and mark the pillar in 1/8" increments until I had increased the VTA by 3°, then repeated the process on the negative side of the zero-point reference. Finally, I made marks between the 1/8" steps. When finished, I had a scale on the tonearm pillar indicating changes in VTA in 0.5° increments from –2° to +3°.

The Stabi's substantial dustcover is easily removed, though after playing records with and without it and hearing no appreciable difference in sound, I left it on and down for all subsequent listening sessions.

Sound

I was totally unprepared for the magnitude of difference I heard between my longstanding reference WTT and the newly installed Kuzma. Every sonic parameter that I placed stock in in assessing the performance of the WTT was redefined by the Kuzma. To say I was astounded would be an understatement. By the end of the first day of listening, I also felt the early tinges of guilt setting in, as I knew that the backlog of reviews I had promised JA were going to be even further delayed. I had favorite records with which to reacquaint myself first!

A then-frequent listening buddy and I were rendered speechless after the fine-line stylus of the Shiraz settled into the first grooves of my mint, promo copy of the El Norte soundtrack (Antilles IVA-4). I guess the silence from which the music arose struck us first—a silence which the WTT conveyed, though not to the same degree as its replacement. The lowered noise-floor of the Kuzma rivaled that of CD reproduction, yet what we heard (or, more accurately, felt and didn't hear) was significantly different from what we'd grown accustomed to with that format. This silence seemed darker, with more "there" there. It was less two-dimensional, less sterile—more, if you will, tangible. Uh-huh!

I know all you doubting Thomases will think I'm speaking in tongues or have spent too much time bareheaded in the California sun when I discuss a seemingly easily grasped concept such as silence using such words as "darkness," "thereness," and "tangibility." How can I describe a sensory phenomenon denoting an absence of sensation using qualitative terms? Simple. I just learned to listen more with my senses than my intellect. It works. In listening to El Norte, for example, it was easy to "visually" differentiate the several venues in which the recordings took place—the soundstage, the field, or the church—by the sense of "silence" unique to each of them, felt when the instruments or vocals stopped and the last decay of the notes faded away. Hmmmm. I guess what I'm trying to say is that the Kuzma, more than any other turntable in my experience, was able to convey the "feel" of the venue in which a recording took place. Be it totally artificial (as found in much electronic music), completely natural (any Water Lily Acoustics recording), or somewhere in between (much popular music), I felt I was privy to the event not as a voyeur, but as a participant.

The Kuzma's soundstaging was as broad and as deep as I've heard, outperforming the WTT. If the WTT presented a view seen through a 28mm lens, the Kuzma widened the field of view to that of a 21mm lens. On all but the best "audiophile-approved" recordings, the WTT sounded congested compared to the Kuzma. With the latter as my analog source, I became keenly aware on recording after recording (audiophile or not) of musical information coming at me from well to the sides and far beyond the loudspeakers. It didn't take long for me to realize that playing records on the Kuzma was akin to doubling the size of my modest listening room! The question as to whether or not that presentation was "accurate" didn't enter my mind—I was too busy listening to and enjoying my records to worry about it. All I can say is that, given the spatial and sonic limitations imposed by my listening room, I never felt that the scale of a performance was sacrificed. Compromised? Perhaps. Nevertheless, the musical gestalt was always preserved (footnote 3).

Instrumental, vocal, and other images within the soundstage had well-defined outlines and were exceptionally well-focused. They were rock-solid and unwavering, presented in a near-holographic manner. For example, the opening drum-whacks on "Huanyo de Zampona," from El Norte, emanated from a precisely focused spot waaaaay back in the soundstage.

Just about any cut from the Emerald Forest soundtrack (Varèse Sarabande STV 81244) provided an object lesson in image specificity. The kaleidoscopic array of instrumental and vocal colors captured in the grooves of this magnificently recorded album hits your ears from all over, under, around, and through the huge soundstage. Each sound, be it a human voice or one or more of a myriad of strange and exotic Amazonian Indian percussion instruments, could be pinpointed in the mix with accuracy and ease—as if composer and musician Junior Homrich had handed me a placement diagram. Fine details were retrieved like crayfish being lifted out of murky pond-water in a nylon net.

I've listened to the title song on Andreas Vollenweider's Caverna Magica (...Under the Tree—In the Cave...) (CBS FM 37827) many, many times—not so much for the music content as for the sound. This recording is a box of sonic truffles, delighting the audiophile's ears much the same way the fungi equivalents delight the gastronome's palate. Neither the WTT nor the VPI Mk.IV (which preceded it in my system) drew me into the introductory "fanta-scape" as compellingly as the Kuzma did. I felt as though I was arm in arm with the anxious (and no doubt giddy) travelers as they entered Andreas's moist, mysterious grotto.

What really knocked me out, though, just as the effects ended and the music began, was my sudden awareness of the presence of a small thing, located about 2' above and in front of the right loudspeaker, that "fluttered" directly in front of my face and over to the left loudspeaker. That got my attention, and that of my two cockatiels, who, perched on my shoulders, were sharing that particular listening session with me.

Bass reproduction on the Kuzma was as good as I've ever heard in the past in my system—robust, full-bodied, and taut. Bass extension seemed limited only by the program material itself. For instance, the well-chosen notes of Charlie Haden's plucked acoustic bass on Rickie Lee Jones's early-'90s Pop Pop (Geffen GEFD 24426) rolled out of the loudspeaker's drivers to fill the room with rich, vibrant sound.

Pitch definition, articulation, and control were such that I could easily visualize the languid vibrations of the acoustic bass's worm-sized, dusty, low E-string. Here again, the Stabi easily upstaged the WTT in this regard, the latter sounding somewhat woolly and undernourished by comparison. Speaking of articulation, I clearly understood for the first time just what happened in the alley with the two-by-four midway through Stevie Ray Vaughan's "Tin Pan Alley," from his hard-driving 1984 Couldn't Stand the Weather (Epic FE 39304).

Conclusion

With the ready availability of compelling and important new popular music on LP (footnote 4), a virtual endless supply of excellent, inexpensive used LPs of all genres—and the superb Classic Records, Analog Productions, Mobile Fidelity, Cisco Music, and other reissues—music-lovers convinced of the virtues of vinyl playback have an unprecedented opportunity to indulge their passions and bask in the warmth and honesty of today's cutting-edge analog reproduction.

I know of no better way of taking advantage of this vinyl renaissance than with the Kuzma Stabi/Stogi combo. For three grand and change you get a superior-sounding, no-nonsense turntable willing and able to convey all the dynamics, dynamic range, rhythm and pace, nuance, and finesse which are the stuff of music. And, it's built to last into the next ice age.

If you match and mate the Kuzma combo with a good medium-output MC cartridge and a great-sounding, relatively inexpensive phono preamp such as the Ensemble Phonomaster or Michael Yee Audio PFE-1, you'll hear what's given rise to all the brouhaha.—Guy Lemcoe

Footnote 1: I wish other tonearm manufacturers would follow this practice. In my experience, few pivoted tonearms indicate just where the arm's pivot point is, making cartridge overhang an educated guess at best.

Footnote 2: I found that an additional counterweight was needed to optimize bias on cartridges weighing less than 6gm.

Reviewer: Ken Micallef

Digital Source: McIntosh MCD 201 CD/SACD player, Oracle CD 1500 [in for review]

Analog Source: Kuzma Stabi/Stogi turntable/arm combo, Denon DL-103 cartridge, Auditorium 23 Denon step-up transformer [on loan]

Preamp: Shindo Allegro

Amp: Art Audio Diavolo [in for review], Art Audio Symphony II [in for review]

Speakers: DeVore Fidelity Super 8s

Cables: Auditorium A23 speaker cables, Crystal Cable Micro Speak interconnects

Stands: Salamander rack, 2" Mapleshade platforms (8" x 15" x 2"), Blue Circle custom amp stand

Powerline conditioning: JPS Labs Kaptovator, Shunyata Black Mamba and Anaconda Vx Powersnakes, Hydra 4 [on loan]

Accessories: Mapleshade Surefoot and Heavyfoot brass points and IsoBlocks; (8) RPG ProFoam damping panels/ceiling treatment, Mapleshade Ionoclast for static cling

Room size: 24' x 12', short-wall setup

Review component retail price: $1,750 for table in brass, $1,000 for arm

Even in today's digitally dominated world, you can find practically a hundred turntable manufacturers in as many far flung lands. And talk about bargain to balderdash prices. $250 will buy you a pleasurably purposeful turntable from Rega or Music Hall; $1500 gains entry into more significant surroundings from J.A. Michell, Roksan or Thorens; many mad, mad thousands can be spent on super machines from Brinkmann, SME, Walker, Grand Prix Audio and Continuum. Add a cartridge -- say a $40 Grado Black or a $10,000 Clearaudio Insider Gold -- and you'll wonder if the fans of this supposedly antiquated technology (who prefer analog any day over CDs, downloads and iPods) have lost their minds, their wallets and the children's college money. Or just perhaps, they are onto something?

It only takes a brief listen to a quality turntable, say the Rega P2 outfitted with a Grado Black cartridge, to turn a skeptic into a believer. Not only can used LPs be had for dimes on dollars these days but vinyl holds charms to soothe the savage breast and the digitally aggravated ear. Digital technology has certainly evolved since the late '80s but vinyl still accomplishes something only more expensive CD players and SACD discs can claim. Sure, you don't get the gut- busting, feet-scorching bass reproduction of digital but that is more than accounted for with vinyl's deeply layered, palpable soundstage and exceedingly natural sound. Music just sounds more whole when played back via vinyl and turntable: the ear relaxes, music flows with an exceedingly rightness of feeling (not to mention a larger, more deeply layered soundstage). And some would claim that vinyl-enabled bass is more accurate than the gobsmack-to-the-gulliver of digital. Damn though if we don't get tired of changing LPs. Yet there is undeniable magic in the analog message.

"We at Kuzma Ltd. have been studying the theory and practise of analogue playback since 1975", states the Kuzma website. "[We are] continually extracting more information from what is nowadays called an inferior medium. There is no known limit to the extent of recoverable information compared to the limits of digital playback. This makes analogue replay closer to the human ear and brain."

Slovenia-based Kuzma Ltd. is a respected turntable and tonearm manufacturer, their goods distributed in the US by www.TheMusic.com, which also distributes vinyl from reissue company Classic Records. Kuzma tables run the gamut (three turntables, three tonearms) from the $18,000 - $19,500 Kuzma Stabi XL and the $3,900 Stabi Wood to the unit under review here, the Kuzma Stabi S turntable and its accompanying Stogi S tonearm. (Smell like a cigar? Nah.)

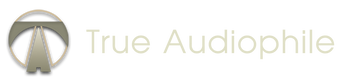

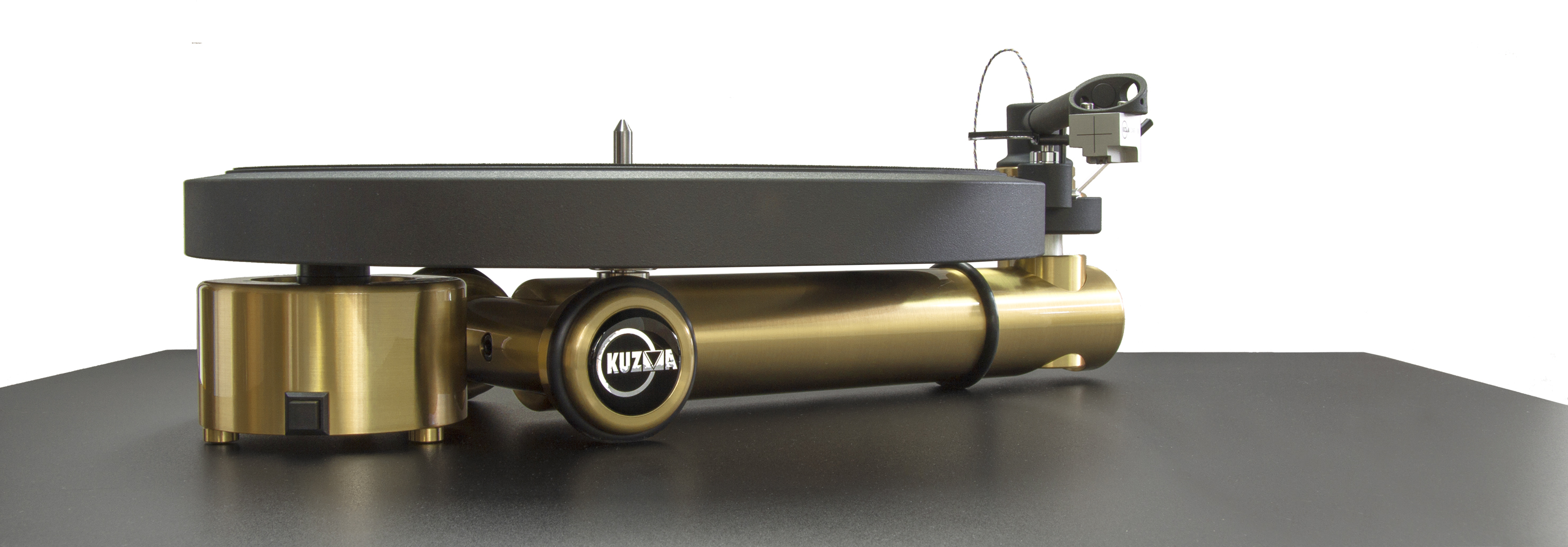

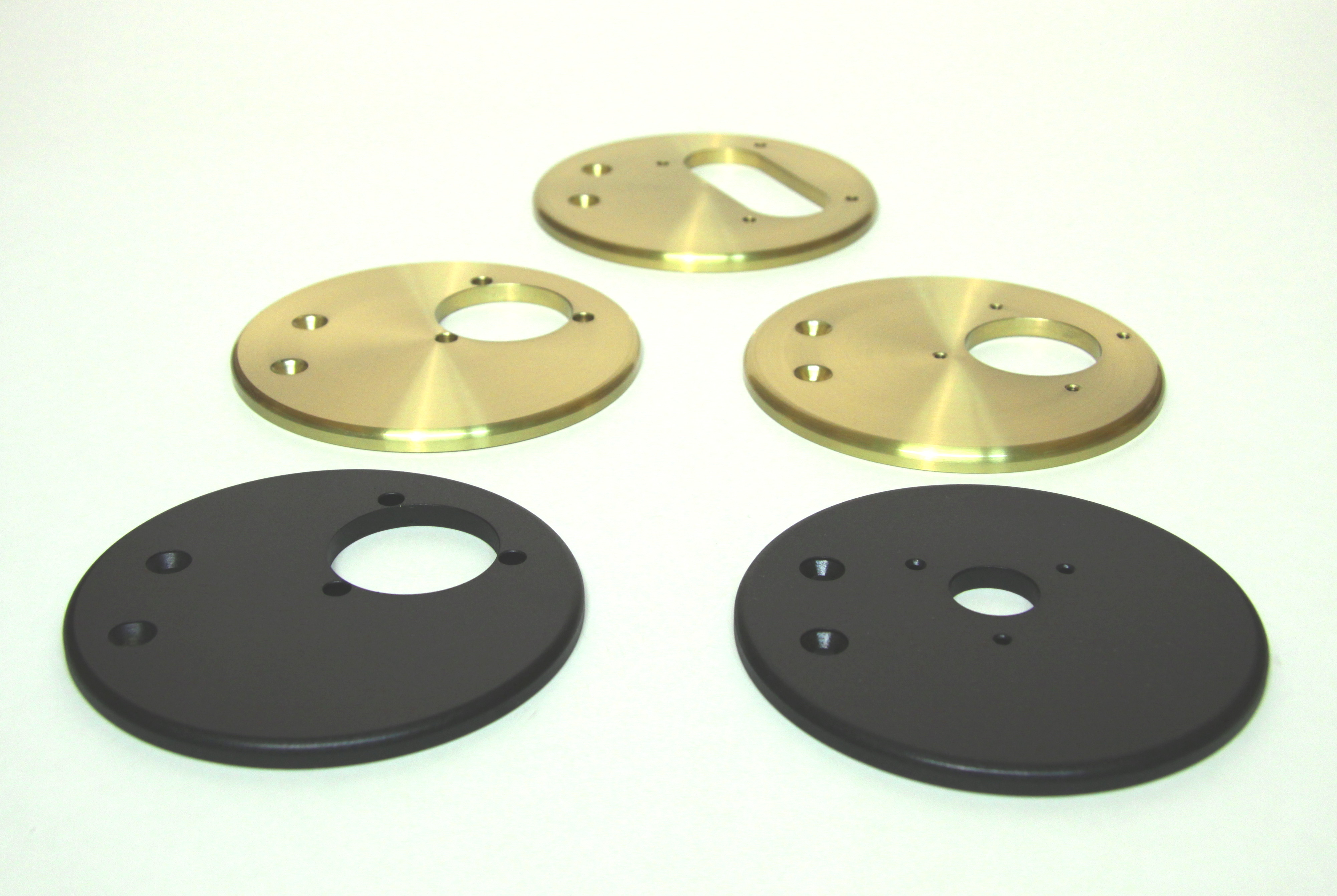

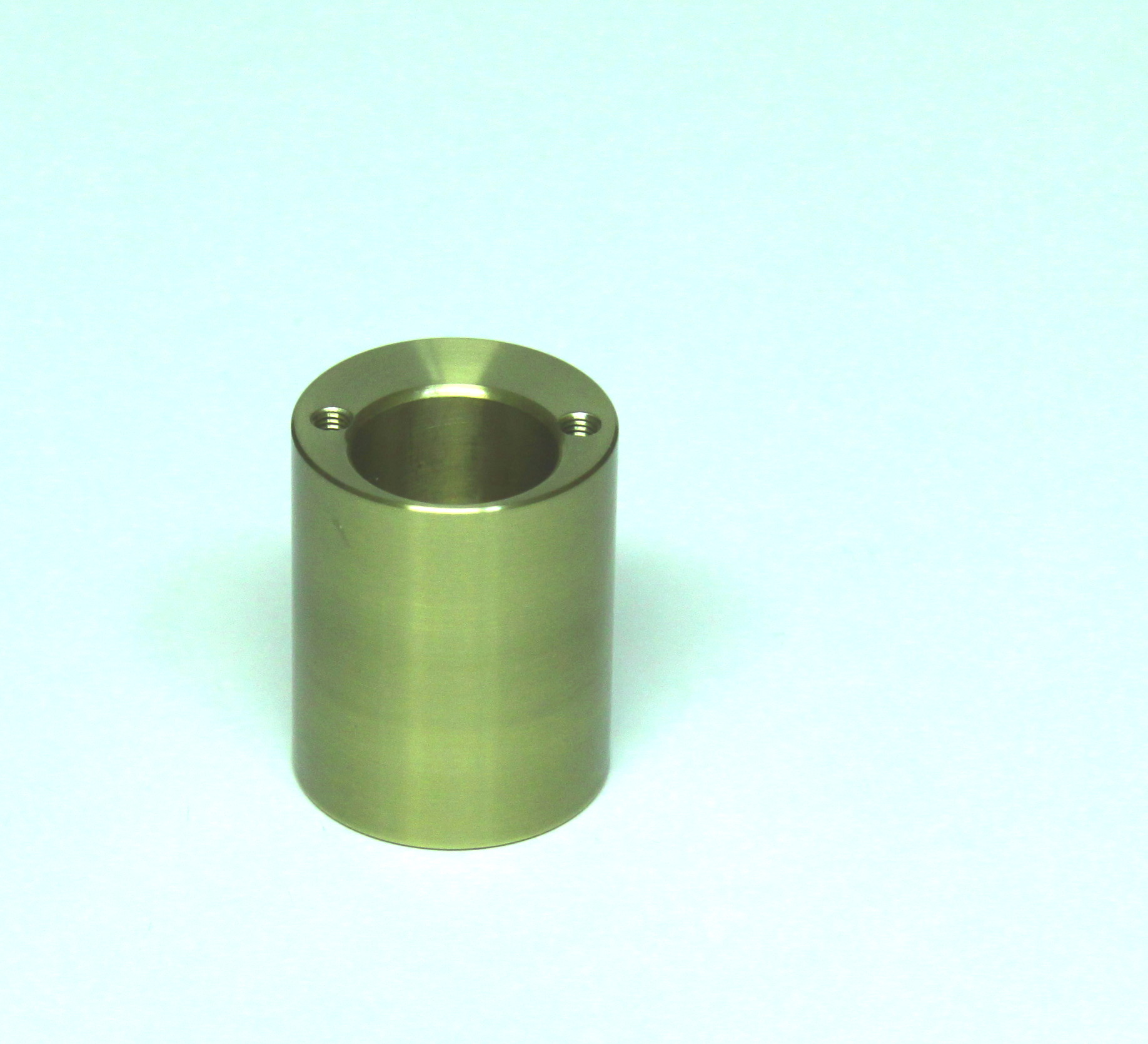

The Kuzma Stabi S turntable looks like no other. There is no conventional plinth or base but instead two interlocking massive solid brass rods connected in T formation which gives the frame high rigidity and resistance to vibration. The motor is housed independently in its own brass biscuit to dampen internal vibrations. The Stogi S tonearm is a unipivot design, its head shell and arm machined from solid aluminum and metal block, respectively. The arm's pivot point is sited in an oil well, which enables extremely low friction and bearing vibration. Silicone damping controls resonance of the cartridge. Internal wiring is in one continuous piece from head shell to RCA phono connectors. Weighing 35 pounds and costing $2,750 for the combo, this is a very well designed, seriously manufactured turntable that has fans all across Europe. Lack of suspension (similar to VPI tables) demands careful placement though. Brass magnet spindle weight is $99.

"The Stabi S is our smallest turntable with a design approach normally found only in more expensive models", reports TheMusic.com's Scot Markwell. "Its unique shape and construction of solid brass rods provide an extremely rigid connection to platter, bearing and tonearm support. There is no flat plate to resonate and transmit vibrations, only solid brass rods 50mm in diameter. A second brass rod provides stability and the two are clamped together in a T shape. A ground, flat belt provides drive from the motor pulley to the sub platter.

"The bearing is of highly polished, fine grain carbon steel", he continues, "with a one point contact, while the bearing sleeve is of a resin/textile material which has excellent damping and non-resonant properties. With a mat on top and rubber insert underneath, the platter provides a stable non-resonant platform for records which, in addition, can be clamped."

The Kuzma Stabi/Stogi combo has been in continuous production for over a decade and the design hasn't changed except for improvements to the bearing assembly and the change from round to flat belt. Kuzma tables are manufactured in Slovenia by Franc Kuzma, chief designer and owner. He has a small work force that does the machining, polishing, assembly etc. both on-site and at various vendors in his area.

TheMusic.com also provided a few extra LP review samples, records familiar to anyone who calls himself or herself a jazz lover: Duke Ellington and Johnny Hodges' Back to Back [Verve MGVS-6055-200gm] and Side to Side [Verve MGVS-6109-200gm], and John Coltrane's Live at the Half Note One Down, One Up [Impulse! B000-2380-200gm]. These LPs feature Classic Records' 200gm Quiex SV-P vinyl formulation.

Upon dropping the needle (a Denon DL-103), it was instantly apparent that there is little semblance between the domestic CD releases and the Classic Audio LP reissues. The sound of live performance, of flesh and blood musicians breathing in and out as portrayed on the Kuzma equals and in some cases surpasses anything I have heard on CD or SACD. Granted, we are talking about a posh turntable linked to equally expensive ancillaries (yes, my rig!), but analog sound is not about dollars but a difference in medium, in presentation of texture, of small details that result in superior realism, completeness and faithfulness to the recorded event.

Side by Side is a jam session of sorts, featuring the cream of Ellington's 1950s sidemen including the great rabbit himself, Johnny Hodges. Also jamming are Harry Edison, Jo Jones, Roy Eldridge, Billy Strayhorn, Ben Webster and Wendell Marshall. The mood is relaxed and fun and the band is just in top coasting form. That the Classic reissue sounds great is just icing on the cake. First up is the massive bass sound, which in audiophile terms is probably overkill, but I really dug it. Womp womp womp, just mopping up the joint with bass tonnage. Drums are almost distant, reacting with the large studio space while Hodges and Ellington's instruments are front and center, warm and present. When Jones switches to ride cymbal, you can hear it bouncing off the high ceilings and when the band starts to rock, the sonics can sometimes become a little stressed but this is a classic, wonderful recording.

More cohesive from an audio standpoint is the sister disc Back to Back, recorded around the same time (58 to 59) with similar personnel. Drums take a similar highly resonant position throughout and the bass is not quite as overwhelming, but the lead soloists are much better recorded and resolved. There is no hint of strain anywhere here and the music is equally relaxed and delightful. The Kuzma detected every subtlety in each of these LPs and presented a fully cohesive, very dynamic and tonally accurate picture of the music. These are two must have discs for those who love easy swing played by the masters.

Coltrane's Live at the Half Note/One Down, One Up is an entirely different beast of analog gaiety. This long rumored to exist 1965 recording features one of Coltrane's most heralded solos in the title track, plus the sound of drummer Elvin Jones keeping time purely on cymbal and snare after his bass drum pedal breaks mid-song. At 27:40, "One Down, One Up" has a flow that recalls Live At Birdland yet with more control and less bombast. At one point, Coltrane and Elvin dive into a duet for a full 15 minutes until Elvin's pedal gives out which doesn't deprive the music but only alters its colors. Originally a radio broadcast, the audio can sound small at times but remastering gives full reign to Coltrane and pianist McCoy Tyner, with Elvin's fury barely contained. Still, it's a historical recording which reveals the quintet in a transitional period not long before the departure of Elvin and the full-on, interstellar space jazz immersion of Trane's final period. Again, the Kuzma got to the heart of the music.

The Kuzma Stabi S/Stogi S combination is a hands-down winner, and in my opinion, one of the world's great turntable bargains. It played every piece of vinyl put to it with a welcome wink-wink nod-nod and proceeded to reveal its true nature, good, bad or glorious. It performed flawlessly, ran up to speed quickly and was relatively easy to set up. And I liked its streamlined dust cover the most. Ignore this Slovenian mini miracle at your own peril and be forever doomed to the trash heap of lousy digital. We wouldn't want that for you...